Why is Sake so expensive?

At most places in Europe, you will have to look long and hard to find a bottle of good Japanese sake for less than EUR 30, a daiginjo will easily cost EUR 50 and more.

Compared with wine, this puts sake in a price range which most consumers only buy for special occasions, but not daily drinking (The “sweet spot” for most wine drinkers is around EUR 15-20 for a bottle). If we follow this chart from Wine Folly, sake falls in the “Ultra Premium” or even “Luxury” segment.

The high price also lends an air of exclusivity to a product that is already perceived by some as a drink for insiders. Price is often a major factor keeping people from trying different kinds of sake (or buying any sake at all).

But how do these prices come to be and much of that money actually goes to the brewery?

EUR 12.00 for a good bottle of ginjo!? Not in Europe

If you compare the price for a 720ml bottle of Japanese sake from various breweries, you will find that the retail price in Europe is almost double that of Japan. Dawazakura lists a suggested retail price of JPY 1,300 for their classic ‘Cherry blossom ginjo’. On Rakuten Japan it is available for JPY 1,400–1,500 or roughly EUR 12, while it is sold for EUR 35 at a major European online shop – almost three times as much. Similarly, Hakkaisan’s futsushu (regular sake) is available for around JPY 1,000 for 720ml, in Europe you’ll have to be lucky to find a bottle for less than 30 EUR.

How do these prices come to be?

Generally it can be said that the retail price of Japanese sake largely represents the actual cost of the product, i.e. the price of a bottle is determined by labour and material cost rather than marketing or hype. High-priced sake is almost always made from highly polished, top-quality rice and/or using labour-intensive brewing techniques.

The Development Bank of Japan has a handy graphic that shows the price structure of a 1.8l bottle of regular sake (futsushu).

Regular sake (futsushu), retail price JPY 1,890/1.8ℓ

For reference, a good quality estate-bottled Bordeaux costs about EUR 2.50–3.00 per 750ml bottle to produce.

Extrapolated to a 1.8l bottle that would be around EUR 6.00 or JPY 760.

According to this chart, the cost for rice and materials adds up to JPY 349 per bottle, labour adds another JPY 349 – so the total production cost is JPY 698 per bottle or approximately 37% of the retail price. The profit margin for the brewery in this example is JPY 300 or 30%, resulting in a price of ca. JPY 1,000 when the bottle leaves the brewery.

It is important to note that this example price structure is for the lowest grade of sake, which can be produced at large volumes with the help of automated processes and from relatively cheap ingredients (e.g. using regular table rice instead of special sake rice). Economics of scale also come into play – a small brewery will need to pay more per unit for packaging and materials than an industry giant buying larger volumes.

Brewery giants use automated processes and cheaper ingredients to produce large volumes at low cost.

Smaller breweries often rely more on manual labor, which will increase labour cost. Both during the brewing process, where big companies can afford helpers such as automated rice steaming machines, but also during bottling, labelling and packing. Many small and quality-conscious breweries still do everything by hand.

In addition, using labour- and time-intensive brewing techniques, such as kimoto or yamahai, will result in an increased price. This is also true for specialty styles like kijoushu and koshu (aged sake).

Many breweries do everything by hand – from carrying rice bags to applying labels.

“A 60 kg bag of rice for sake brewing can range from JPY 15,000 – 27,000 and more”

From the graphic above it is clear that the biggest cost factor for breweries after labour cost is the rice. An this cost can vary quite substantially, depending on rice variety, quality grade and polishing ratio: A 60 kg bag of rice for sake brewing can range from JPY 15,000 – 27,000 and more (actual prices vary every season). Now imagine that you are polishing that expensive Special-Top-Grade, Hyogo-grown Yamada Nishiki rice down to 35% of its original volume to produce daiginjo – suddenly the cost for rice alone will be over JPY 1,000/bottle (1.8l). This is an extreme example, of course, but it’s fair to assume that the rice is responsible for JPY 400-500/bottle even for a mid-range sake.

Making high quality sake is not cheap. Production cost in JPY/liter

Lastly, around 35–50% of the price are wholesaler’s/distributor’s and retailer’s margin. In the example above, the brewery’s margin is ca. 30%. Most breweries aren’t exactly cash cows, so this margin might be considerably less for some products. After all, you don’t see many brewery owners driving fancy cars and living large.

Hype and speculation

Since most sake is meant to be consumed within a year or so after production and does not improve with time, even the most premium sake does not invite the same kind of speculation and like fine wine or Japanese whisky, which have seen steep increases over the past 10–15 years. Only very few sakes are sold, or re-sold, at prices that equal prestigious wines.

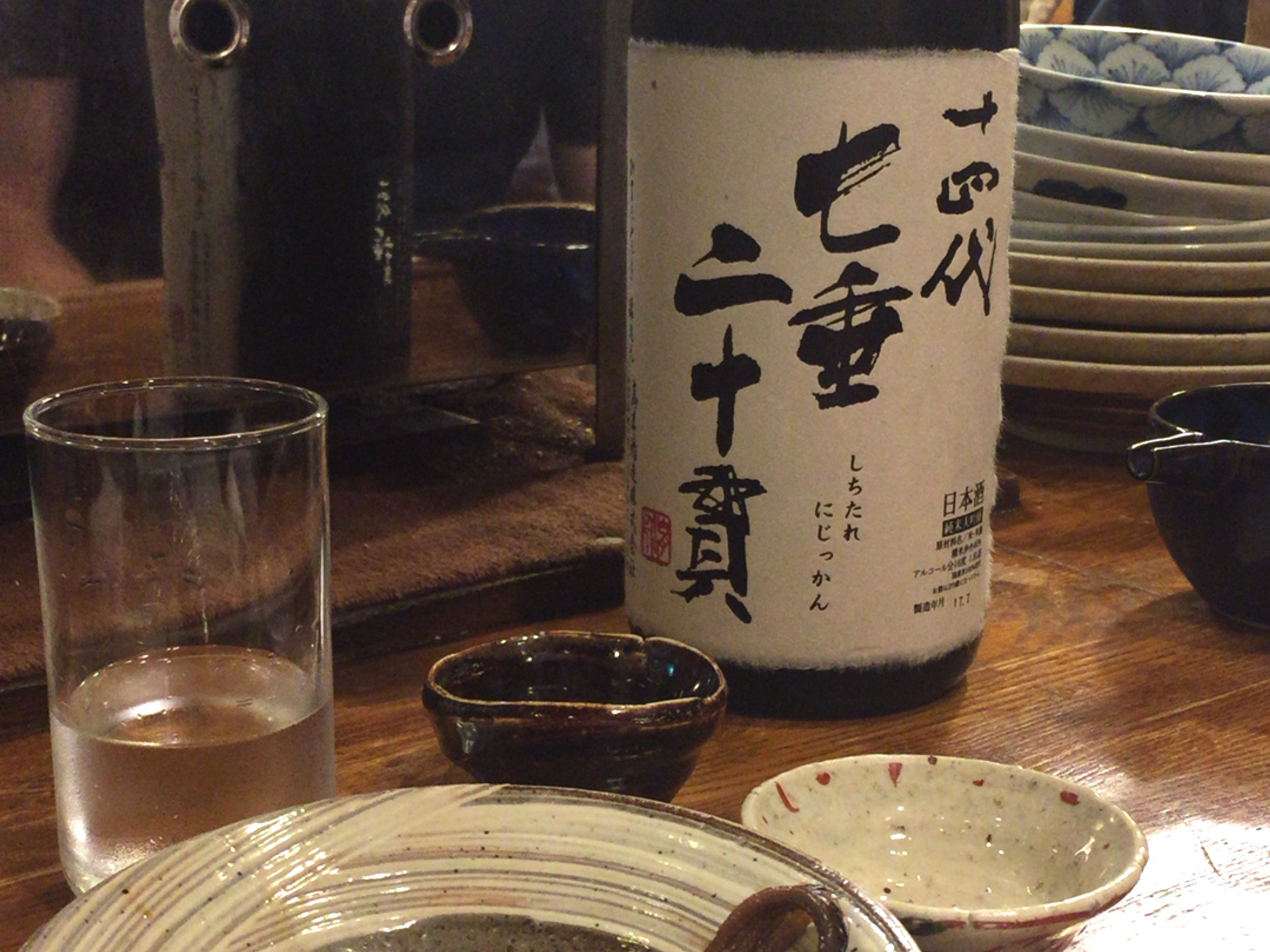

The somewhat secretive Takagi brewery in Yamagata has long had a large group of devoted fans and produces a wide range of mostly junmai daiginjo sake under the name Juyondai (十四代 / 14th Generation). It’s a brand that is almost impossible to buy in shops.

On online platforms like Rakuten and Yahoo these bottles are sold for JPY 40,000 and (sometimes a lot) more, but they actually have much lower retail prices set by the brewery. Juyondai and similarly popular brands are best enjoyed at izakaya and sake bars, where you can drink them by the glass at much more reasonable prices. Many producers are quite critical of the high resale prices that some sakes fetch at online shops and on the secondary market – they want their product to be enjoyed by people who appreciate the craft of brewing.

Limited releases and super-popular brands like Juyondai are best enjoyed at izakaya.

Every once in a while, a brewery might release a super-limited ultra-premium sake, like Tatenokawa’s Kyomo with a rice polishing ratio of 1% (recommended retail price JPY 110,000, roughly EUR 838). But these are more marketing and “see-what-we-can-do!” than real products.

Before you spend several hundred Euros on a bottle, keep in mind the law of diminishing returns also applies to sake!

So why does sake cost more in Europe?

A unique price factor for sake sold outside of Japan is of course import, i.e. international shipping and any applicable taxes/tariffs. Sake is a perishable product and is best shipped refrigerated, especially if you want to import delicate daigino or even unpasteurised sake.

At current rates, sending a pallet of sake in a reefer container from Osaka to Amsterdam costs around EUR 1,600 plus duties, handling charges and transport to and from the port. If we assume 660 bottles (720ml)/pallet that’s at least EUR 2.50 (ca. JPY 300) per bottle.

Import duties on Japanese sake have been eliminated with the EU-Japan EPA, which came into effect in March 2019. Local taxes apply, but in Europe these are not higher than those on wine and generally on a similar level as in Japan.

The last factor then is simply a higher margin for both importers and distributors as well as retailers. This might in part be due to the increased risk that goes along with importing and selling sake outside of Japan.

Sake is still a niche product in Europe and consumption is limited to a relatively small group of people. Even those who enjoy drinking sake might only buy a few bottles a year. There’s always a chance that an importer who bought a large batch of Japanese sake might be left sitting with unsold stock that is deteriorating in quality and value a year later. (As is evident from the many bottles in European shops with production dates going back one or two years; something you never see in Japan.) Many importers and retailers also invest a lot of time into passionately promoting sake – efforts that might not always see an immediate return.

“Sake is generally priced very fairly.”

In the end, it must be said that sake is generally priced very fairly. With the exception of a few well-marketed super-premium products, you get what you pay for. And there are many great sakes in every category (even simple futsushu!) that punch well above their price point.

With most sake, you get what you pay for.